Jan Tomasik, the man who built Scotland

by Leszek Mazan July 18, 1981

transated by Wojciech Szczerek

The author of this article never felt an urge to walk high mountains – reaching the summit of Giewont left him fully satisfied. Until he managed to climb the highest peak in the UK, Ben Nevis (1345 metres above the sea level) that proudly towers over the Grampian Mountains, on foot within a few minutes and to be able to see almost all of Scotland: from the Atlantic to the border River Tweed.

All this thanks to the modest one-time bricklayer from Kraków’s Krowodrza, Mr. Jan Tomasik, the owner of Scotland (in miniature).

As the story goes, Jaś Tomasik was born on the outskirts of Kraków called Krowodrza. He studied a bit closer to the centre of this famous city but acquired his profession according to Krowodrza’s tradition: through bricklaying. When he had already achieved not only the professional title of a master builder, but also had become a company co-owner, World War II broke out and Jaś – or actually Jan at that point – set off to fight the Germans. His regiment repaired bombed bridges and rail tracks in Lesser Poland. This period did not last long as events proceeded very quickly. Wounded in the Battle of Lwów he was taken to a camp in Hungary, escaped, reached Yugoslavia and then France. He served in General Maczek’s division, was wounded a second time and was evacuated to Scotland along with thousands of other Polish soldiers. Here, he married a Scottish lass and went back to the front again. He completed the whole liberation campaign from Normandy through northern France to Belgium and the Netherlands, always at his general’s side, towards whom he felt the deepest respect and sentiment, both then and now. In 1945, he came back to the British Isles. The United Kingdom gifted him – as a veteran payment – £45 and ten shillings, but the British government would not allow him to get a job in the construction industry. So, Jan started mopping floors in Edinburgh’s hotels.

The floors were concrete and the hotels’ standards were very poor. Because he worked with his wife, doing 20 hours per day, and saved every penny – after only 3 years he purchased a complete ruin, dirt cheap, and turned it into one of the most popular hotels within a few months. He stayed at this charming hotel with his wife, Katarzyna, who was even more hardworking than himself, he paid all debts on time, never hired people for work because everything – from hammering in nails to serving champagne to the guests – he did by himself. As a result, after several years he already had more than a dozen hotels, while the local newspapers would more and more often refer to him as the “prince of the Scottish hoteliers, Mr. Tomasik”.

In 1970, the “prince” went for a weekend trip to the mountains and just a few tens of miles south of Edinburgh in the middle of a forest on top of a hill he saw this old and abandoned castle that was falling apart. It was the Black Barony – shrouded in legend and the mist of history – the old seat of the Murray family. He drove up closer, looked around, climbed the ladder leading up to the top of the ancient tower and decided, “Kasia, we’re buying!”.

The Black Barony, in the condition Jan found it, was built in 1536, but the traditions of the Scottish family who, here, in the hills, remained resistant to the English as early as the 13th century, something that the new owner and the heir of the legend would not refrain from emphasizing on each and every occasion. It was here that the gatherings of the Scottish Highlanders and the secret deliberations between clans took place, while the prisoners bound in heavy chains howled at nights. On the upper floors, rivers of the best, the most original Scotch would flow. Births, weddings and deaths as well as the victories and defeats were celebrated. The most disastrous of defeats, the Massacre of Glencoe in 1692, marked the end of the Murray family’s prosperity and, many decades later, opened up the Black Barony’s gates to Mr. Tomasik. The original clan owner, as well as the castle, had long fallen into decline. Its owners had changed through many “barons” over the decades.

Mr. Tomasik, as the story goes, bought it, paid in hard cash and got right to work, of which there was plenty to do. Yet again, all bricklaying works he did almost by himself, the historic buildings inspector did not interfere too much, only sending three letters containing the overview plans of the Barony and asked him to pull down less and fix more. No-one would check whether this favour was being fulfilled as Jan was a justice of peace for 21 years and commanded profound respect and trust. He also had – something that the inspector did not know about – a sentiment for the history brought to the Scottish mountains all the way from Kraków. As a result of all interventions the castle’s walls were renovated and fortified in a fashion that would make them sustain the most severe of the English sieges, the chambers were decorated as if it were for a Murray family convention, or even for the visit of the Scottish King, while the stocks in the cellar were treated with rust preventive paint. Jan decided to share his new mansion with weary travellers and established it as a hotel with a restaurant. The business prospered greatly, the rooms were so occupied that Jan had to purchase a luxurious mansion in the neighbouring village and move there with his family.

But for him this was still not enough. He decided to have all of Scotland.

It so happened that Baron Tomasik had attended Kraków’s schools together with the present celebrity in the world of geography, Prof. Mieczysław Klimaszewski. During the professor’s visit to Scotland to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of St. Andrews, Klimaszewski paid his former classmate a visit and helped him fulfil his dreams of power: “He wants Scotland, he will have it!”. Shortly after the visit, two geography scientists from Kraków (Kazimierz Trafas and Roman Wolnik) came to the Black Barony, while lorries unloaded 500 tonnes of cement in front of the castle. A dam was built at the crystal-clear stream that flowed around the mansion in order to feed a decent-sized lake. On the lake – listen! listen to this! – a concrete island was built: a miniature model of Scotland, created with great accuracy at a scale of 1:10,000. The heights of the mountains were exaggerated by five times following the cartographic convention for topographic models.

So, in 1980, the Baron and I are leaping over the North Sea and we’re marching along the Caledonian Mountain range to finally reach – after walking some 12 metres – the neighbouring range of the Grampians. Below us lie green forests, yellow valleys and red mountain peaks. The off-shore Outer Hebrides are glinting at a long distance, Edinburgh and Glasgow are shining in the sun, the lines of roads and rivers are sectioned by the network of viaducts and bridges.

“This cost me a whole lot,” sighs Mr. Tomasik. “’This country is all mountains and it took more concrete than I had thought it would. But I can tell you one thing – no other country in the world has such an attraction, such a map.”

True, true, this is no fantasy talk, everything had been designed with scientific precision, the concrete, the colourful plastic or the steel that keeps the whole thing strong have not been spared. Of course, the owner would not allow just anyone to walk all over Scotland so blithely. You normally get to see it from the shore of the lake, but this is still a big attraction, same for the impression. This is confirmed by coach trippers that keep arriving at the Black Barony, with an appropriate fee being paid each time. “All income goes to the charity,” says Mr. Tomasik. “May Scotland have something from me.”

Supposedly, even this year on the embankment, just off the Hebrides, a modest, yet visible sign will be put up: “To Poland, so many kilometres.” The distance is calculated by the Barony’s owner often as he used to be the member of the Polish Olympic Committee, he was even encouraged to buy off – for a symbolic 1 zloty – a few castles from our government. “Please, Jan, even just one!” The Baron even started seriously considering this proposal, but when he learnt about all the preservation requirements, construction law, the user’s duties as well as the fact that in 10 years the renovated castle would have to be taken from him, he backed off.

And he stayed in Scotland, at the Black Barony. After finishing our walk over the map, he took us to the wonderful park, where at the roots of old elms whole generations of Murrays lay. A newly engraved marble plate stood leaning against the gate of this cemetery park: “Jan Tomasik, born 1914, died at the Black Barony, … .”

Over the entrance to the Barony, the visitors are greeted with the white eagle on the red background, Polish flags fly above the corner towers, the interiors of the lounges are densely decorated with medals from general Maczek’s division, who, by the way – well, such is life – used to be employed by his former subordinate for some while. The subordinate also believes in the regularity of the wheels of history “and, you know, I will live till the day when a school in Poland is named after my general, after this wonderful commander and great Pole… .”

We sit down under the emblem of Maczek’s famous brigade, Jan pulls out the old Scotch, the type you don’t dare dilute with water, and he talks and talks and talks. About his life, about how he misses the country, about Krowodrza and his children whom he has already moulded into adults a long time ago, about his Barony and the big map on the lake, where the other part of the island, England, will soon grow. Relaxed tourists crowd outside while the executioner’s chains clank in the casemates (fortified parts of a stronghold/castle), and I couldn’t leave without asking:

“The castle is haunted, of course?”

“Of course.” Jan livens up “It’s haunted alright! The White Dame in the Black Barony herself. I can even tell you she started picking up some Polish… .”

LESZEK MAZAN

Photography Franciszek Palowski

__________________

Jan Tomasik, A Soldier for Poland

It’s Spring 1939 in Poland and the sun is back. It’s warm enough for Jan Tomasik (left) to remove his coat as he supervises work on a building site in the district of Nova Huta on the eastern outskirts of Krakow. The sky is blue but soon the dark clouds of war will presage the gathering storm.

Krakow, August 1939. Jan has answered the call to arms. His country will soon be at war but unable to withstand the combined might of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. The future looks uncertain.

But the fight goes on. France 1940 – “Poland has not yet perished”. Jan stands in the centre of the group, his face sideways, looking down. No-one foresees the events of May and France’s rapid defeat.

The Fall of France sees Polish soldiers evacuated from Dunkirk and rescued by the Polish Navy from the ports of western France. Many make their way to Britain whichever way they can. These ones have set up temporary camp at Crawford, Lanarkshire in September 1940, and are enjoying a Royal Army Ordnance Corps band in full ‘Swing’ at a camp concert.

It’s October 1940. The place, Douglas, Lanarkshire. Jan (3rd from left) and his comrades are settling in to a new life they hadn’t planned for. They’re on their way to hear a lecture given at the local coalmine.

On the move again, this time to Barry Buddon camp near Carnoustie in Angus. It’s October 1940 and the Poles have been deployed to strengthen the defences of this part of Scotland’s North Sea coast. New barracks have to be erected to accommodate the sudden influx of men. Jan lies on his stomach looking at the camera during a short meal break. The British Army like the camp so much, they call it “Barry Butlins”. But it isn’t home.

It’s December 1940 and the Poles’ first winter in Scotland. The cold isn’t a problem, but the wind…! It may be a long time before combat equipment arrives, but Jan already has a vehicle, perhaps to carry out the kind of duties that will lead to him becoming a quartermaster later in the war.

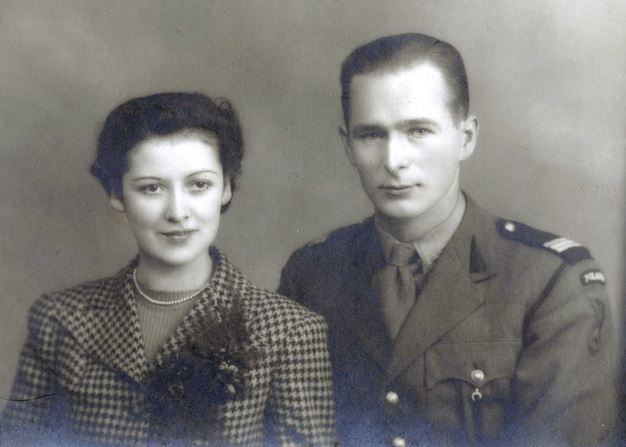

It’s the biggest day in anyone’s life, and a time to put the war to one side for a brief moment. Jan Tomasik of Krakow, Poland is marrying Catherine Kimlin of Edinburgh, Scotland in Galashiels in September 1942. Note the ‘Poland’ patch and ‘Winged Hussar’ insignia of the 1st Armoured Division on the shoulder of Jan’s tunic. The three stripes on his epaulette show he is a lance-sergeant.

Romance blossomed for Jan and Catherine in 1942, but the autumn leaves on the banks of the Tweed in October are a reminder of impermanence. What lies ahead is unknown. Sooner or later the Allies will open up a Second Front in the West and Jan will go. Whether he will return only God knows or Fate will decide.

Newmarket, Suffolk, July 1943. The Division has moved south for training. After a few months the men will return to Scotland and await the order to liberate Europe – “For Our Freedom And Yours”. Jan marches proudly with his comrades-in-arms (3rd rank from the front, in the centre and instantly recognisable by his moustache). He will be one of the lucky ones. He will return. Others in the photograph will not. Many lie today in cemeteries like the Polish-Canadian Military Cemetery in Breda in the Netherlands. Jan will hear his commander, General Maczek, say “The Polish soldier fights for the freedom of other nations, but dies only for Poland”, and he will know the truth of it.

View the same pictures as a slide sequence:

Our thanks go to the Tomasik family for supplying these photographs.

_________________________

Tomasik the business man

From the Glasgow Herald, 15th May 1990

Winners and losers in the Black Barony affair

As Harry Cathcart, director of the Hill Samuel merchant bank in Scotland, said when I phoned him for a quote about the following story:

‘This isn’t the Diary’s usual light-hearted stuff. Won’t your readers find it hard going?” Probably, for we are talking here, as part of an ongoing series in the Diary, about accountants, banks, and other financial institutions and what happens to people when they find themselves in the hands of these

professions. It is the story of Jan Tomasik and his bitter experiences at the hands of the professional classes.

Mr Tomasik is a well-known figure in the entertainment and leisure business in Glasgow. He worked with various hotel groups, ran a number of successful pubs, but was probably best known as manager of the Apollo Theatre in its heyday. He sold his Shadows bar in the city to concentrate on creating a country house hotel at the Black Barony, an old mansion house in Eddleston, near Peebles in the Borders. The bulk of the money was raised through the Business Expansion Scheme, where investors receive significant tax incentives to put their cash into projects. This was his first, and salutary, lesson in how expensive professional services can be. Professional fees — lawyers (two sets; one Scottish, one English because the fund-raising company was based in Birmingham) accountants, and fund-managers — came to £400,000. A large chunk of the £2m required to get the plan from the drawing board into existence. The share issue went well and raised in excess of £1m from small investors. The largest shareholder, apart from himself, was in for £7500. The rest of the cash for the project was to be raised from the banks.

Mr Tomasik, through contacts, was invited to meet Hill Samuel, the merchant bank which is part of the TSB. After a lunch (for which he picked up the bill) and further negotiations, Hill Samuel agreed in October 1987 to put up a £650,000 loan and give #200,000 overdraft facilities.

As well as the interest, Black Barony plc was charged £10,000 by Hill Samuel. Mr Tomasik recalls this being described as a placement fee. Mr Harry Cathcart of Hill Samuel tells the Diary that this was a 1% ”commitment fee” and is standard practice when you borrow money from merchant banks.

There was also a 2.5% interest charge to be paid on money which was not taken up immediately. This, in merchant bank terminology, is called a non-utilisation charge.

At this stage, Mr Tomasik was not deterred by such charges and was busy overseeing the construction work to turn the old country house into a hotel. This was duly done by the target date of May 1988 with the construction work completed within £20,000 of the £1.15m budget. Mr Tomasik then set about building up the reputation of the Black Barony, aiming for the main markets of business conferences, weekend breaks, tourism, and local functions. With its luxurious facilities, the hotel was given three stars by the AA with an invitation quickly to apply for four stars. Mr Tomasik says he was perhaps over-optimistic in his projections for occupancy rates in the initial opening period. But, he claims, business was picking up on all fronts when, only eight months after opening, his financial backers began to make nervous noises about the safety of their investment.

By March 1989, Hill Samuel’s nervousness was translated into action. Mr Tomasik says that he realised that matters had taken a serious turn when Hill Samuel bounced Black Barony cheques to suppliers. He tried without success to speak on the telephone to Mr Ian Barnet, Hill Samuel’s commercial lending manager in Scotland. Late that afternoon, he received a telephone call from Mr Barnet informing him that Hill Samuel had decided to call in a company of chartered accountants to put the company into administration. Putting a company into administration is a relatively new procedure, a variation on receivership or liquidation. The result is almost as devastating forthe individuals involved.

Mr Raymond Blin, an insolvency specialist with accountants Pannell Kerr Forster in Glasgow, arrived that evening at the Black Barony to take over the running of the business. Mr Tomasik says he found Mr Blin’s attitude aggressive. ”He said that he was now in charge and I could stay on in the interim and do things his way or I could go down the drive there and then.” Mr Tomasik decided to stay on and run the hotel under the accountants, hoping to find a way of saving the business. He already had hopes of persuading the shareholders to put more cash into what, he says, was a business on the upturn. The hotel was fully booked for the Easter weekend, only weeks away. The bookings for functions and conferences were healthy. The cash flow was not good. But the company had not used up its full £200,000 overdraft facility with Hill Samuel and had not missed any repayments on its term loan. There then followed a difficult time for Mr Tomasik. He was in charge of running an upmarket hotel but had to refer to an accountant, one of Mr Blin’s Edinburgh staff, for every purchase. As standing orders to suppliers had been cancelled, the propane gas supplier had not been paid and the Black Barony was left without supplies of fuel for the kitchen but with a hotel full of people to feed. There was also the personal ignominy when J. A. Cathcart, the Glasgow auctioneers, were called in to put a price on everything in the hotel. Could Mr Tomasik prove that the John Byrne portrait of Billy Connolly (a present from the days when Jan was part of the Big Yin’s management team) belonged to him and not the hotel? Did Barony, the yellow Labrador pup which Mr Tomasik had bought when the hotel porter’s bitch had a litter, belong to him or the hotel?

Meanwhile, as well as running the hotel, Mr Tomasik was trying to put together a package to buy the hotel back from the administrator who had put the business up for sale as a going concern. His hopes in this respect were shattered in June of 1989 when the hotel was sold for a sum of £1.3m.

On June 18, two lawyers, a representative from Pannell Kerr Forster, and two sheriff officers arrived and requested Mr Tomasik to leave the premises. Mr Tomasik says the outcome of the period of administration was that Hill Samuel received all their money owed to them; a brewery which had a secured loan of £100,000 received their money in full; and Black Arrow, a company which had leased furniture to the Black Barony received 90% of their money and entered into a deal with the new owners. While all the large secured creditors emerged unscathed, the small businesses due money were not so fortunate. Mr Tomasik lost all his own investment of £90,000, not to mention two years of intensive work. Pannell Kerr Forster received almost £60,000 for their work as administrators. Mr Tomasik says he met Mr Blin only once and his Edinburgh colleague eight times.

The Black Barony is still trading under its new owners and, by all accounts, is thriving. Mr Tomasik says they should be, starting with a clean sheet and a hotel, bought for £1.3m with a potential gross profit of £1m a year.

Jan Tomasik is back in Glasgow, running a pub. He feels that the accountants and merchant bankers did well out of the affair. To be more exact, he says: ”I feel we were raped by the system.”

* Mr Cathcart of Hill Samuel told the Diary that the bank had put the Black Barony into administration to prevent other creditors from putting the company into receivership and harming prospects of keeping it as a going concern.

* Mr Blin declined to comment on the amount of remuneration received by Pannell Kerr Forster.