Story of the Map

“The Great Polish Map of Scotland” was built over six summers between 1974 and 1979. It was mainly the work of a small group of Poles from the Jagiellonian University of Krakow, Poland, led by the map’s main designer, Dr. Kazimierz Trafas. They were assisted by staff from the Hotel Black Barony (Barony Castle) and Polish exchange students visiting Britain.

The map was the brainchild of Krakow-born Jan Tomasik (pron. Tomaashik), a sergeant in the 1st (Polish) Armoured Division, who had been stationed in Galashiels and had married a Scottish nurse in 1942 after being treated in the town’s Peel Hospital for the effects of a wound. This photograph shows him on a building site in Poland in the 1930s.

He became a successful hotelier in Edinburgh after the war and added Black Barony to his properties in 1968.

In the early 1970s, during a ‘thaw’ in the Cold War between the Soviet Bloc and the West, Tomasik met Professor Mieczyslaw Klimaszewski, head of the Institute of Geography at the Jagiellonian University of Krakow and proposed his idea of creating a large physical relief map of Scotland in the grounds of his hotel. Cartographer Kazimierz Trafas, newly awarded his doctorate, took charge of the design work and arrived in Scotland in 1974, accompanied by his colleague Roman Wolnik. The project was managed and supervised by Tomasik’s son-in-law, hotel manager Marek Raton, who, along with the hotel’s maintenance man Bill Robson, did much of the basic construction. The labour was partly supplied by Polish exchange students seeking casual summer employment during their time in Britain.

Various influences seem to have led to the building of the map. It is known that Polish soldiers made an outline map of Poland on the ground, with towns and rivers marked, at their military camp at Douglas in Lanarkshire in 1940. This is the camp where Jan Tomasik was first stationed after his arrival in Britain. It is also known that he was fascinated by a miniature scale-model map of Belgium which he saw at the Brussels World’s Fair (Expo 1958) on his way to visit relatives in Poland in 1958. This apparently inspired him to create something similar in the grounds of Barony Castle. He wanted the map to show hotel guests the landscape of Scotland and hoped it would become a tourist magnet. He also said that he wanted to show the coastline of the country Polish forces had been responsible for defending during the war and that he hoped Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI, would officially open the map. He is remembered as saying to hotel patrons, mainly neighbouring farmers, on more than one occasion, words to the effect, “I shall die, but I shall leave my map as a gift to the Scottish people to thank them for the hospitality they showed the Poles when it was needed”.

The Great Polish Map of Scotland measures some 50 metres by 40 metres and lies in an oval pit surrounded by a 142 metres long perimeter wall. Covering an area of 1590 square metres, it is understood to be the largest three-dimensional physical representation of a country and the largest outdoor relief map in the world. (see more about its size here)

Building the map posed a formidable challenge.

In the summer of 1974, the Polish cartographers surveyed the site and undertook the layout of the map. The topsoil was removed and the shapes of the mainland and islands were marked out to a scale of 1:10,000. Then three contour lines of 300, 600 and 900 metres were laid in brick courses with vertical shuttering to contain the concrete infill.

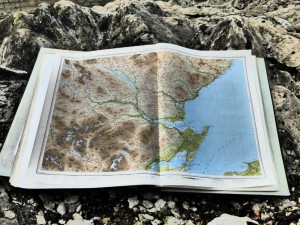

The following year Tomasik drove the hotel’s transit van to Krakow, returning with Trafas, Wolnik and three hired employees from the University: Janusz Szewczuk, Zygmunt Olecki and Jerzy Zelech. This time Trafas brought with him a small scale model he had made to guide the construction. He created it by applying new techniques of three-dimensional machine modelling, first producing a gypsum model from which a plastic mould was made which was transported to Scotland in four parts. The cartography was taken from a volume of maps from the Edinburgh atlas publishers, John Bartholomew & Sons (this was discovered in the hotel in 2003).

The body of the map was gradually built up, followed by the difficult task of manually sculpting the terrain. Mountain summits were marked by vertical wooden rods, their height exaggerated by a scale of 5:1 to enhance the visual impact (a standard traditionally adopted for military relief models during the war). Work resumed in the summer of 1976 when the topography was completed and the map painted with an undercoat.

courtesy of http://www.peebles-theroyalburgh.info/great-polish-map-of-scotland

courtesy of http://www.peebles-theroyalburgh.info/great-polish-map-of-scotland

In 1977 and 1978 work continued, but at a slower pace, and by 1979 the basin wall, begun earlier, was completed. Soil excavated from the basin, which had been piled around the perimeter, was now landscaped to form a gently sloped banking. The surface of the map was coated in a resin compound and painted grey. Geographical features were added by painting forests green, outlining the major cities in light brown and painting the major roads red, including those running through cities. Rivers and lochs were painted blue. Water from the nearby Dean Burn was piped to the basin to form the surrounding seas, with narrower submerged pipes supplying the sources of the major rivers.

In 1981 deterioration of the surface paint caused by weathering was tackled in an general attempt to refresh the map. The existing paint was stripped and the whole map repainted. The photograph below shows new undercoats being applied. A hotel fire in the same year and the pressing need to renovate the damaged interior diverted attention and efforts away from the map.

The map being repainted in 1981. The photograph was taken from a roof next to the oldest part of the castle, the north tower.

After the hotel closed in 1985 and ownership of Barony Castle passed from the Tomasik family, the map fell gradually into neglect and disrepair caused mainly by frost damage. It became heavily overgrown and almost hidden from sight.

On a later visit to Scotland in 1994 Professor Trafas, as he now was, happened to mention the map while attending a European Union sponsored meeting of town planners from Edinburgh and Krakow. Its “rediscovery” led eventually, in 2010, to the formation of Mapa Scotland, a group of volunteers dedicated to saving it from further decay and restoring it to its former condition. Pre-launch displays to attract support were held in Penicuik Town Hall on two Saturdays before the Mapa Scotland inaugural meeting and Open Day at Barony Castle on Sunday 25 April 2010. In August 2010 the initial clean-up started. Category B-listed status was secured for the map in 2012. In September of the same year it was the subject of a debate in the Scottish Parliament sponsored by Christine Grahame MSP. (The proceedings were simultaneously translated into Polish; the first occasion they had been simultaneously translated into a language other than Gaelic.)

In 2013, while the search for funding continued, work began on clearing loose rubble and weeds from the map in advance of restoration, and tests were carried out successfully to reconnect the old gravity-driven water supply.

In the same year Mapa Scotland acquired charitable status. Its main aim in restoring the map is to ensure that it becomes a permanent feature in the Borders landscape and an educational resource and visitor attraction for future generations to admire and enjoy. The map’s construction, and now its restoration, have linked Scots and Poles for almost three generations.

Restoration was completed in December 2017. A grand opening ceremony and reception was held on April 12th 2018.

https://www.facebook.com/TheScottishGovernment/videos/1685197728201732/

* * * * *

Mapa Scotland thanks Jan Tomasik’s son-in-law Marek Melges for his valuable assistance in the writing of this article.